New Series on Craig Keen's "After Crucifixion" (1)

The first in a series of posts on this extraordinary book!

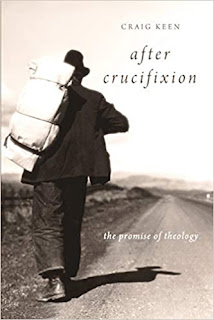

After Crucifixion:

The Promise of Theology

by Craig Keen

(Cascade Books,2013)

Many books on the market these days advert to their

intention to offer a “future,” or a “New Direction(s),” or address the

“promise” of theology for the age and in the world we live in. Craig Keen’s is

no exception as his subtitle shows. The difference, in my view, is that his

succeeds as few others do. And in a way none of them do. That he claims the

cover picture of his book – a hobo (I presume) walking down the side of a

freeway, knapsack over his shoulder, road signs too far off in the distance to

make out – conveys the message he wants to share (Kindle loc.173) already

points to the “weird” (loc.70) introduction to theology on offer here.

In this first post I will reflect on Keen’s own reflections

on what he has done in his rather fulsome “Preface.” In following posts I will

move through his text chapter and interlude by chapter and interlude.

In this extremely evocative text Keen hones an approach to

the peculiar enterprise that is Christian theology. God has created to be

“thinking bodies,” as Keen writes in the Preface and his style and presentation

reflect that dynamic Michael Polanyi termed the “tacit dimension” to all human

knowing: that we know more than we can say. Meaning is a personal transaction

between thinking bodies that depends as much on our embodied-ness as on

explicit communication. Keen draws on an image I well remember to illustrate.

Awkward Jr. High boys crossing the dance floor to ask a girl to dance. Our bodies do indeed communicate some of that

more we know but cannot say.

Unsurprisingly, then, Keen says he writes as invitation to

his readers to join him in a dance, a “perichoretic” dance (loc.70). A dance

that is prayer that invites a partner to join in its articulation in hope that

God may choose to answer it. As he eloquently explains,

“This is not actually a book about anything . . . It is

rather a book of something . . . What I have written, more particularly, is a

prayer, a prayer I have prayed precisely in the writing . . . It prays

performatively, as an act, as a movement that perhaps without presumption might

be called a dance, a perhaps perichoretic one, if the epiclesis of God’s good

pleasure happens to be answered. It is a dance, though, that calls for a

partner. Which means that this is that awkward moment when I stand before you,

having crossed the wide well-waxed hardwood floor, and ask with downcast eyes

if you would dance with me” (loc.70).

Nevertheless this book is academic

theology, a theology of the “cross” (loc.137). A theology that asks, wonders,

prays what life “after crucifixion” for the church in our world might look

like.

“Everything we might say, this declaration as well, is

entangled in an overtly or covertly memorial past and a wonderfully or

fearfully anticipated future. . . Thus the words to come are to be read as

moving without nostalgia or expressive spontaneity or the calculative drive of

purpose or ataraxic mindfulness. They are to be read as expenditures with

neither deep pockets nor favorable investment prospects. They are to be read as

invocations and supplications toward an event in which the fruit of the

knowledge of good and bad will have been unhanded” (loc.128).

Two important words for Keen appear here. The words

“expenditures” (we might well say “offerings”) and the goal of theology as

“unhanding” its works. We have little to offer in our doing of theology, but we

give what we have which may amount more to giving up even the little we have to

see and hear more clearly what is given us to say.

This “weird” (and wildly refreshing) introduction to

theology has six chapters, intervening interludes, and a prologue and a

postlude. The prologue (which Keen tells us says what he wants to say along

with the book cover) we will start with and work through each chapter and

interlude through to the postlude. Here’s how Keen describes his chapters:

The first chapter is a “personal” but not “autobiographical”

introduction which tells “something of the history from which this discourse is

set to task. It makes clear that somebody wrote this book, even if he wrote it

by no means as its chief protagonist and author.”

In chapter two theological method is on the table. Keen

wants to both say and to show “something of what (and how) ‘after crucifixion’

entails.”

Chapter three takes up the work of liturgy, the formal

liturgy of worship in continuity with the everyday work that sustains our life.

All work, all liturgy, ought “to be an expenditure of thanksgiving, every day

of every week.”

An eschatological account of bodies, or “resurrection of the

flesh” in the subject of chapter 4. Keen pithily sums it up as confessing “a

future in which the whole damned world will have been emptied, the way a large

cage might be emptied of a captured pelican, say, were its barred walls, floor,

and ceiling suddenly unhinged at their right angles of intersection and cast

away.”

Chapter five is about martyrdom. This is, for my money, the

heart of the book. What might it mean for a church to take the theology of the

cross so seriously that it envisions martyrdom as its destiny. I can’t imagine

a more pertinent question!

Theological education, if Keen believed in it, would be the

topic of the sixth chapter. He doesn’t believe in it because he doesn’t believe

in “leadership,” “especially on leading the ignorant from darkness to light. I

am not sure how that kind of exitus is compatible with the good news that the

God we are to follow is the God who is with us irruptively. The task of

learning well before the bread and the wine of the eucharist (the bread and the

fish of the wilderness feedings) is the task of learning to live with those,

let us say, who have been left behind.”

We’ll get to the interludes and postlude when we get to

them. Not because they are less important – not at all. But because this is

enough, I trust, to whet one’s appetite for the whole work.

Comments

Post a Comment